British Vogue, 2008

Nick Knight is perhaps one of the most prolific and innovative fashion image-makers of our time. He has worked with just about every notable name in the fashion industry, from Alexander McQueen, John Galliano, Rick Owens and Comme des Garçons, to name just a few. While you may not know his name, you’ve undoubtedly seen his work: arresting, sometimes otherworldly images and films in countless fashion magazines and advertising campaigns as well as music videos and album cover art for the likes of pop stars David Bowie, Lady Gaga, Kanye West and Bjork. His still and moving imagery evokes a pseudo-animated world that verges on the surreal, and consistently blurs the lines between traditional photography, art and image-making itself. Reality is far from the point: Knight freely uses digital manipulation and retouching in his work, which is why he prefers to be known as an image-maker rather than a photographer. He’s responsible for pioneering the genre of fashion film and for creating SHOWstudio.com, where he live streams photo shoots in an effort to “show the entire creative process from conception to completion” and collaborates with creatives from all walks of life to create a continuing dialogue around fashion. For his first solo exhibit over a career that spans four decades, he decided on the name “Nick Knight: Image” to frame the vast body of work on display at the Daelim Museum in Seoul, Korea. In an exclusive interview with S/ magazine, the creative visionary speaks about his inspirations, the creation of his iconic online platform, and collaborating with the great Alexander McQueen.

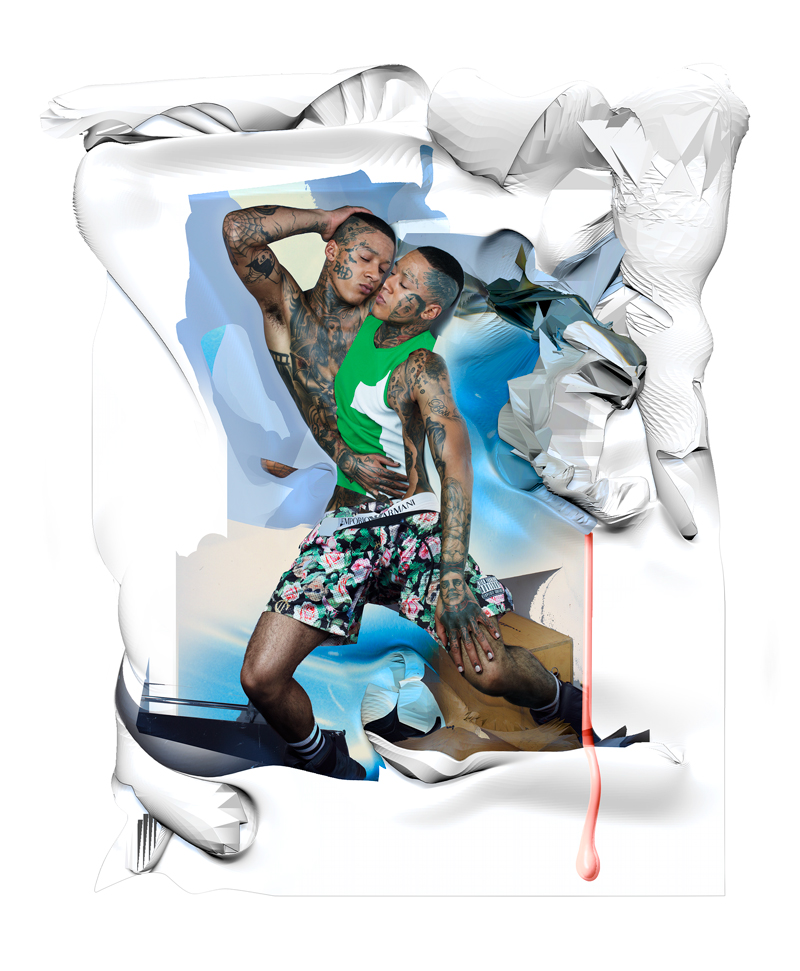

Blade of Light, Alexander McQueen, 2004

Blade of Light, Alexander McQueen, 2004

On choosing image-making over a career in medicine:

“It was about 1978/79 when I realized I wasn’t going to be what I thought I was going to be—I wasn’t ever going to be a doctor because I didn’t have any real desire to spend my whole life studying and wanted to go out and do other things and experience life and photography seemed something that would allow me to do that. I’d always presumed, like my parents and like my brother, that I’d have a career in sciences but I got sort of side tracked in my studies to try to get into medical school and discovered photography, which I thought it was exciting and interesting and therefore couldn’t be considered serious work. I went to an art college on the south coast of Britain called Bournemouth which was very experimental and had unstructured lessons. That’s when it occurred to me that I had a love and a passion for it but also that I didn’t really have a choice: make a success of this, or there’s really not much else for you. So I looked back at all the other photographers who had ever worked [such as] Muybridge and Stieglitz, which I thought were great, and I thought: ‘I can do better than that, that’s not that impressive. Surely if I work as hard as I can every hour that God sends and never ever stop then I’ll be able to do it.’ Now, 30 or 40 years down the line, it’s still basically how I work; if you can put everything you possibly can into making that image the best image in the world, and not get side tracked in any way, then usually you get something at least worth looking at.”

On desire, curiosity and how a fashion image comes into being:

“Normally what sparks it is desire. Desire, intrigue, curiosity and wanting to experience something that I haven’t experienced before or see something I haven’t seen. So normally desire is the initial spark, and then there are people who I’m excited by, whether they’re models or designers, or whoever. I try to get these other people to see how I can see my desire and imagery can fit into their desire to see their collection or whatever it is, whomever I’m working with. It’s also curiosity. Photography and image making gives you a passport into other peoples’ lives, which could be the Prime Minister of Britain or it could be the President of the United States or it could be a prostitute, it doesn’t really matter. Whoever you’re interested in, you can usually get to them through photography because it’s a way you can approach people and say ‘hi, you don’t know me, but I’d like to take your photograph,’ and nine times out of 10, people will let you into their lives. You showing interest in somebody is usually enough for them to invite you into their life.”

On image-making versus photography:

“Well it’s not a particularly good term to be honest but I call myself an image maker. I think it’s an important point because it’s about the future. If you came from Mars and I described to you what photography was, you’d understand it, you’d get it and you’d be able to link all those early photographers (from Muybridge to Mapplethorpe). Now in the early to mid-90s, we have a change in how you create imagery, the revolution that goes hand in hand with the birth of the internet, a new platform to have a new art form, the global instant interactive platform. All of a sudden you’ve got something that’s a very new as a way of putting material out there and a new way of creating material. Now you can take a picture on your iPhone or your mobile phone and you can now put it into an app and move the image around as if it’s paint, or you can make it into three dimensions–all of these things are really outside the boundaries of [traditional] photography. This new art form, that’s not photography, because [that label] holds back this new medium, which is not even 20 years old yet, because you’re trying to define it through the parameter of an old medium. So I could clearly say I think ‘photography’ died in the middle of the 1990s and a new art form was born. Let’s celebrate it, because it’s much more exciting, and there are many more possibilities.”

On the power and importance of fashion:

“I remember the first time I went to a fashion show, which was 1986, sitting in the front row during the Yohji Yamamoto show and I couldn’t believe how brilliant it was to be there. I looked down the front row, everybody looked so miserable and I couldn’t believe, ‘why are they so miserable? This is the most exciting thing!’ [Fashion is] one of the most exciting, creative industries, and what you see every six months is an outpouring of creativity across the planet on the catwalks and you see these designers pouring their visions to the world and yet it’s treated as if it’s something that’s not particularly good, or not particularly worthwhile. Living in England, that’s very much the feeling even the intellectual press, you look at The Guardian or you look at The Times or The Telegraph and it’s pretty much a misunderstanding of fashion. [Fashion] is primarily how we express ourselves, everybody makes a decision on what they’re going to wear because it’s the first thing people see. We know that we’re going to express who we are and so the first thing we do is put on clothes, so that, in some way, says people are artists and some people do it with more skill than others, but it’s still a basic form of human expression; there’s never really been a society that hasn’t used fashion in some way to express itself. In my belief, it’s a very strong art form and super democratic and important through history and continuing is the way we show who we are and that shouldn’t be dismissed.”

On fashion film and the creation of SHOWstudio:

“I think you start from the premise that a fashion designer creates a garment to be seen in movement, always. There’s never been a fashion designer who has created a garment just to be seen in a photograph—they’re always meant to be seen as a moving thing and that incorporates sound and movement. …I started filming all of my photo shoot sessions in the mid 1980s, around 1986/87. I [used] a clunky old video camera on a tripod, and I would film all my subjects with the same lighting I was using to take a still image but it was all caught on film. Through the end of the ’80s and beginning of the ’90s I was saying ‘well, maybe I’ll be able to show this fashion and movement’ and I was going to send out a VHS cassette [of the shoots every month]. Then luckily in the middle of the ’90s, the Internet was born and [suddenly] you have a global distribution system that could, at that time, download a little tiny bit of moving image. But I knew you would be able to soon download 15 or 20 seconds of moving image in a very easy way for people to see it and it became obvious that it was a platform it could be shown on. The Internet is a two-way medium, so we started thinking, ‘okay let’s capitalize on that! Let’s work on this new medium, a two-way medium that can show film.’ What I saw was performance, it’s fashion theatre or fashion performance and if you can imagine being in the same studio as Alexander McQueen as he’s trying to sculpt a model into a particular form, that’s something you probably would’ve liked to have seen. We started live-broadcasting our shoots, so live broadcasting and fashion film became the reason for SHOWstudio because it was possible with the Internet being the medium.”

On painting as inspiration and his work as art:

“I’m influenced by many different art forms, but obviously paintings have a very rich and full history, and it’s been used throughout the years to express a whole range of things. So it’s not surprising that it influences my work because with photography and image making, you can change it and move it around the same way you can for a painting, you can open it up and deconstruct it and reconstruct it in all different forms in the same way you can in a painting. A lot of things are much more clear in painting and the history of painting because we have so much more experience and intellectual understanding of it so that becomes very inspiring. [With] any form of art, it’s about self expression and therefore as the boundaries between the arts collapse and dissolve, looking at people who, like myself, there’s a sort of rough feeling at the moment that actually, we are all artists and there isn’t really a [sense] of defining ourselves beyond that. Art is about communication, it’s about one person saying something through a medium of whatever creative art form they choose; they’re expressing their opinions about the world or about their life so that other people can see and understand them. That could be true of literature or opera or ballet or music or any of the other art forms, so therefore I think communication is a kind of better way of summing up what we do, rather than the word art.”

On working with the late designer Lee (Alexander) McQueen:

“Lee and I worked together almost since we graduated; we sort of found each other in the way that people who admire each other do find each other. You sort of keep seeing somebody’s work and they keep seeing your work, and you eventually end up coming together. He would send me a fax every so often in the day of faxes and which he would draw on and say ‘Happy Christmas’ or ‘Happy Birthday,’ quite out of the blue, and then we decided we wanted to meet up. From the mid-90s, we started working together pretty much until he died as frequently as we could. I always knew if he called it would always be a really exciting project, I always knew it would be something that would be pushing the boundaries of whatever we’d done before and I always knew it would be difficult but the result would be amazing. He was a very, very strong influence and a very powerful person to work with because he had a lightning ability to see the image before we’d actually finish creating it. He knew what he wanted and therefore my role was taking things further, to take his vision further than he could see it. I don’t know how many projects we worked on together, probably 50 or something like that.

I think Lee’s world was quite dark and I would bring light into his rather dark world and I think that’s what he needed in a way. Lee had a fascination with death because it made him feel more alive and I think that’s true with a lot of people, if you look at any number of Kurt Cobain’s or Jim Morrison’s, or any popular figures who have died young. I think Lee was very similar; he had a huge interest in the dark side of life and in some degrees so do I, but not in the way that he would. I think I always look for the positive in a situation. If he wanted to express something, I would find a way of expressing it that would make it sort of more beautiful than perhaps his way of expressing it. It’s a bit of a big thing to say because he was an incredible artist in the way that he would bring beauty in the world and show beauty where people would see it but he would need somebody to see it for him so he would often say something like ‘okay, I want to photograph people with very strong physical disabilities’ for instance. In the past and in art history, we look back and see people have been represented and it’s always been in a negative light. …In more enlightened times, in the 20th century, people started photographing people with physical disabilities in a more sympathetic way, but never before we did the story together [for Dazed and Confused in 1998] did anybody show them in an aspirational way. I think that’s why he and I worked together well, because I would take an idea like that and say, ‘okay, well why don’t we treat and show these people how we actually feel about them: they’re just as beautiful as Kate Moss or any of the top models or film stars or any of the pop stars that we see because they’re human and humans are innately beautiful.’ So this isn’t about peoples’ physicality, it never is, it’s about how we aspire to be like them and you don’t aspire to be a physical shape, you aspire to be a person. You aspire to be a person, a different sort of human being, whether it’s Jennifer Lopez, Kim Kardashian, or Kanye West, it’s not about physically being the same shape as that person, but you actually want to be a human like they are. It’s a realization that everybody has beauty within them, somebody has to see it, bring it out and show it to other people, and be able to demonstrate it, and that’s, I think, how I worked with Lee. He could see beauty in people but he couldn’t express it through imagery and I could.”

On his passion for fashion illustration:

“In terms of fashion illustration, it’s always something I’ve loved. I remember when John Galliano was briefing me to do campaigns; he would always start with an illustration, whether it be a Rene Gruau, or Antonio Lopez or a Giovanni Bellini. So it’s what I’ve grown up to love and it’s an art form that used to be a very a central part in the fashion world; the fashion editor would sit front row at the show next to the illustrator and that was very much how people would see the first images of the collections back in the ’50s, and ’60s, and to some degree into the 1970s. It wasn’t until catwalk started that they got such a hold on it that the fashion illustrators suddenly found themselves without a job. I always loved the ability of illustrators to sum up the desirability of a dress and that feeling that you’ve got to have that garment, being able to sum up in an illustration felt like a real skill to me and obviously something that I had looked at a lot in terms of my image-making. Then the Internet came along and things like tumblr and Instagram, and it actually found it’s feet [again]. Now it seems fashion illustration is very much back as an art form and there are incredible artists doing it. They’re actually showing a particular moment and a particular time, so when we’re reviewing the fashion shows with live panel reviews, we invite fashion illustrators to come to SHOWstudio so they’re painting while the people are talking about fashion. I’m super excited about creativity and fashion and to have a panel going on discussing the Vetements show, for example, and then you have an artist who’s actually sketching at the same time and then you have one of the designers who’s actually coming in later, that’s the world I wanted to live in, to be surrounded by people who are intelligent and enthusiastic and have a similar sort of love of fashion that I have. So I sort of created the kind of world I want to be in around me.”

On what’s next and looking to the future:

“My only regret is that life’s a bit too short. I’m really interested in working with artificial intelligence—I think there’s something super exciting there. I’m really excited to work to get some more understanding about physiology of our bodies and the science of our bodies in fashion–that’s something I would love to really push because I think there’s a lot more to be learned there. I’m really excited and have been for a while about the fact that we can make physical objects now so that I can create a 3D scan of somebody and make an object from that data. …I don’t want to sound Frankenstein-ish, but we now know that we can print living matter and our sculptures, should they be living, so there lots of boundary-pushing I’m very interested in. I believe that hopefully our society is going through a profound fundamental and colossal change and I think any change is frightening. I [also] think there are a lot more people who are really excited by the future, that’s one of the reasons I decided to have my first exhibition in Korea because I think Korea feels like a full working nation that isn’t looking back to the past and I wanted to very strongly include it in a place that had that love and optimism for the future. There are lots of things possible now that haven’t been possible before which I’m incredibly excited to look and to try to express and try to understand and I think whether it’s sculptural or whether it’s science, fashion or whatever it is, there’s so much left to do. My only regret is that it’ll take another life to find it.”